Main Content

Is the “Invasive Species of the Month” useful to you? Let us know how.

Looking for an outdoor project for yourself or volunteers this winter? You can stay warm by cutting invasive vines and saving trees while you are at it! Controlling invasive vines can help save trees which are vital for capturing greenhouse gases and reducing the impact of climate change.

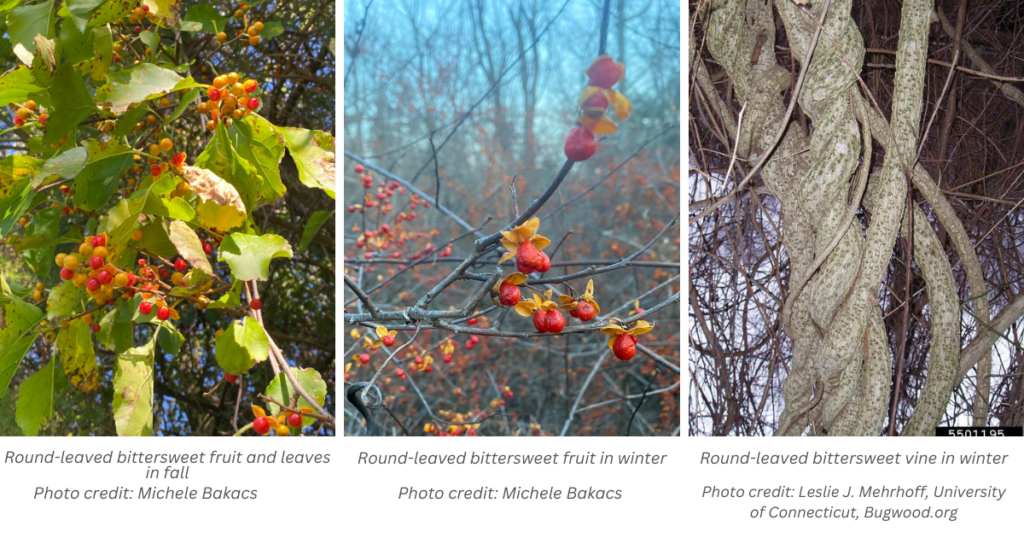

Round-leaved bittersweet, Celastrus orbiculatus, is an invasive vine that climbs, strangles, and smothers live trees. Also known as oriental or Asian bittersweet, it is easy to identify this time of year due to its bright yellow and red fruit that are persistent through the winter and spread by birds. The bright fruit has also made it in demand as a holiday decoration, aiding in its escape into nature. It is popular as a wreath and the seeds stay viable and can sprout when the wreath is discarded. Deer do not eat round-leaved bittersweet and it grows aggressively, smothering native vegetation that is critical for wildlife.

What Makes a Plant “Invasive”?

Per the National Invasive Species Council, an invasive species is one that is non-native to an ecosystem, and causes, or is likely to cause harm- harm to human health, the environment, or the economy. For example, poison ivy, Toxicodendron radicans, can spread rapidly and does indeed cause harm to some people. It is not considered an invasive species though because it is native to New Jersey.

Description: Bittersweet leaves are round with toothed edges, alternately arranged along the stem and between 3 and 4 inches in length. Some leaves are more oval with a pointed tip. In late summer the leaves turn yellow, usually before native plants gain their fall color, making this vine easy to spot from a distance. Yellow-skinned fruit first appear on female plants in late summer in clusters at each leaf axil. In fall the yellow skin splits to reveal a bright red center. Young stem growth is bright green; larger stems have red-brown bark that has a cracked, fish-netted texture. The smooth stems climb by twining or winding themselves around host plants eventually strangling the host.

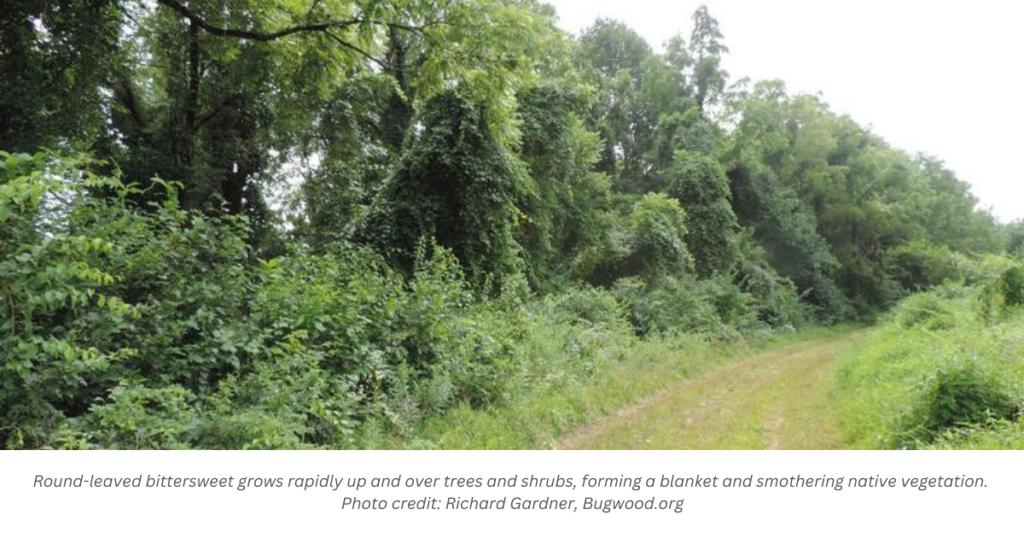

Ecological threat: Round-leaved bittersweet chokes out desirable native plants that wildlife depend on for high quality habitat. This vine smothers shrubs and trees with its dense foliage strangling stems and trunks, especially along forest edges. In some areas, it forms nearly continuous blankets along entire stretches of woodlands. These blankets block sunlight from reaching understory seedlings and stifling natural forest regeneration. Deer do not eat it as they prefer the native vegetation. Invasive bittersweet can grow in shade but prefers full sun and can tolerate a wide range of conditions.

Method of spread: Round-leaved bittersweet was introduced as an ornamental plant as its brightly colored yellow/red fruit made it popular for wreaths and other holiday decorations. The fruit escaped into natural areas and spread aggressively. A single vine can reach 60 feet in length. As a perennial, it puts on yearly growth and can reach diameters of over 10 inches. Round-leaved bittersweet spreads by seeds eaten by birds and by sprouting from its underground root system.

Look alikes: Native American bittersweet vine, Celastrus scandens, is uncommon in New Jersey. The fruit of the native bittersweet is larger than the invasive bittersweet and has a bright red covering instead of yellow, clustering at the end of the branches.

Other invasive vines: Other invasive vines that strangle or smother native plants in our region include five-leaved akebia (Akebia quinata), porcelainberry (Ampelopsis brevipedunculata), Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), kudzu (Pueraria montana), two wisteria species (Wisteria sinensis and Wisteria floribunda), and English ivy (Hedera helix).

Removal method: NOTE! Make sure to bag and dispose of holiday decorations containing round-leaved bittersweet in the garbage.

For mechanical control, small infestations can be repeatedly cut until the roots are exhausted over many growing seasons. When vines are growing up trees, using a window-cut approach is an excellent method for killing top growth. This involves cutting the stem low to the ground and then again at chest height. Do not pull vines down from the tree but rather allow the top growth to die to avoid hurting the tree or yourself. DO NOT compost the seeds or cuttings. Early detection/rapid response is the ideal method for control; learn to identify this vine in small, seedling stages and monitor at-risk locations regularly.

Note that round-leaved bittersweet is difficult to control with mechanical means alone due to its extensive root system. An excellent method of control is to combine mechanical and chemical methods by pre-cutting the vine early in the season and then chemically treating the re-sprouts later, after July 1. Roots will re-sprout if left in the ground without chemical treatment. For chemical control, foliar applications with a glyphosate/ triclopyr mix are effective when leaves are present and after at least 8 weeks of growing time. Cut-stump or basal bark treatment may be difficult with many, smaller stems but is effective on larger stems. Always follow the herbicide label instructions; the label is the law.

Post treatment, make sure to monitor the area for re-sprouts and new individuals for multiple seasons. For more information on control strategies and herbicide application visit Penn State Extension.

If you are not able to or are not comfortable using herbicides, but have an invasive bittersweet invasion that needs attention, hire a landscape professional that has a pesticide license and specializes in invasive plant management.

Native alternatives to round-leaved bittersweet: Do not use ornamental decorations with round-leaved bittersweet. New Jersey has many native vines and vegetation that have winter interest and work well if looking for replacement species for holiday decorations.

Red osier dogwood, Cornus sericea has red stems and is often used for winter cuttings. This shrub does well in full sun with moist soil but can tolerate part shade and drier conditions. It has two seasons of interest with beautiful white flowers in the spring and red stems in the winter.

American holly, Ilex opaca, is a classic for holiday decorations due to its red fruit and spine tipped leaves. It does well in dry, acidic, soil and likes full sun but will tolerate shade. It is deer resistant.

Winterberry holly, Ilex verticillata has bright red berries that stay persistent on the stem in winter. This shrub does well in more acidic, to moist to average soils, in full sun to part shade, and can grow from 6- 10 feet. When male and female are present, female plants will have red berries in the fall and winter. It is deer resistant.

Christmas fern, Polystichum acrostichoides, is an evergreen, clumping fern, whose fiddleheads are silver in the spring. It prefers part shade to shade conditions and dry to moist sites. It is deer resistant.

Little bluestem, Schizachyrium scoparium, turns copper-yellow in the fall and persists through the winter. It is a clumping grass with blue stems during the growing season. It does well in full sun, in dry soil and is drought tolerant and deer resistant.

Thank you to our reviewers: Michael VanClef, Roslyn Dvorin, and Trish Maguire

References and other resources:

Templeton, S. et al., 2020. Invasive Plant Fact Sheet: Oriental Bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus). The Pennsylvania State University Code EE0391. https://extension.psu.edu/oriental-bittersweet

Bakacs, M. and Errickson, W., 2023. Invasive Plants and Native Alternatives for Landscapes. Rutgers Cooperative Extension Fact Sheet FS1353. Available at https://njaes.rutgers.edu/fs1353/

New Jersey Invasive Species Strike Team Fact Sheets. Available at https://www.fohvos.info/invasive-species-strike-team/fact-sheets/

Read past issues of “Invasive Species of the Month”

The goal of Rutgers Cooperative Extension’s “Invasive Species of the Month” is to highlight those organisms that are non-native to New Jersey and cause economic or environmental harm, or harm to human health. We can all help prevent the spread of invasives by learning which species are a threat to our ecosystems.